Disclaimer: The contents and opinions of this blog post do not represent the views or values of Honours Review as a publication.

All right, let’s say you’re an avid reader and love F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). Or maybe Fitzgerald isn’t really your thing, but you simply can’t get enough of E. A. Poe’s short stories.

Now, how would you react if Jay Gatsby suddenly started walking down the streets of Yokohama and, or wait, let me rephrase this. How would you react if Jay Gatsby suddenly started flying above the streets of Yokohama in Moby Dick with Herman Melville, E. A. Poe, and Mark Twain aboard, while H.P. Lovecraft is wading in the Tsurumi river below them, after having transformed into a giant, humanoid octopus?

Well, these are all pretty mainstream events in Bungo Stray Dogs.

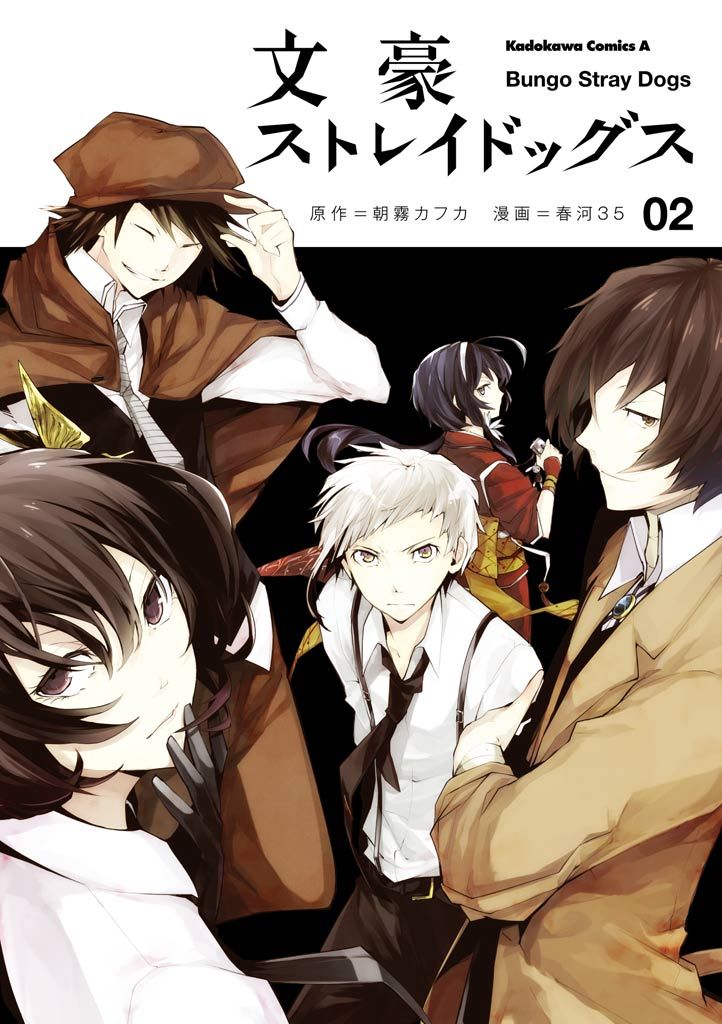

Cover of Bungo Stray Dogs volume two.

Bones studio’s Bungo Stray Dogs (lit. Literary Stray Dogs), a popular Japanese anime series which originally started airing in 2016, is making a big comeback with its third season this April (1). The otaku fandom is naturally excited; it has been almost a year since the series’ last movie adaptation, Bungo Stray Dogs: Dead Apple (2018), was released, and the adaptation, by introducing a bunch of new characters, excellent villains, and a fairly complex plot, only left us with much more questions than it answered.

Bungo Stray Dogs is based on the supernatural action manga of the same name that follows a group of skilled agents gifted with supernatural powers which they use to solve mysteries, fight Yokohama’s underground mafia, and occasionally blast a building or two into the sky.

But apart from the crowd that is regularly engaged with Japanese animation, Bungo Stray Dogs has a lot to offer to audiences that are not that well versed in Japanese anime and manga culture. Above all, it offers them a crash course in Japanese, American, and Russian literature.

Written by Kafka Asagiri and illustrated by Sango Harukawa for Young Ace magazine in 2012 (1), Bungo Stray Dogs is probably best known for basing its characters on famous writers and their books, such as Osamu Dazai, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, E. A. Poe, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and F. M. Dostoevsky. While each Bungo character represents a particular writer, their supernatural power is in one way or another connected to that writer’s works.

This way, for instance, Bungo Stray Dogs’ Osamu Dazai (all characters are actually called the same way as the writer they’re were based on), one of the series’ central figures, was inspired by the early 20th-century Japanese writer Osamu Dazai, author of The Setting Sun (1947) and No Longer Human (1948). The writer had a short but turbulent life: he lived during the two world wars, experienced a series of more or less serious diseases, wrote a number of novels and short stories whose popularity quickly turned him into a celebrity and attracted a secret admirer, regularly enjoyed way more sake than is advisable, and attempted to commit suicide several times until he finally succeeded in doing so in 1948, together with his wife Tomie Yamazaki. Inspired by these elements from Dazai’s life, Bungo’s Dazai is, as a result, constantly preying for a partner to commit a double suicide with, and his special ability, which allows him to cancel other ability-users’ power, is called “No Longer Human”, just like the ‘real-life’ Dazai’s famous novel.

Similarly, one of the series’ main antagonists, the Port Mafia member Ryunosuke Akutagawa, is based on the Japanese writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa, “Father of the Japanese Short Story”, whose famous works include Rashomon (1915), Hell Screen (1918), and In A Grove (1922). Many of Akutagawa’s stories are characterized by their macabre character. Rashomon, for example, is a story about an encounter between a servant and an old woman at the southern gate of Kyoto, where corpses were sometimes dumped. Hell Screen recounts the life of the painter Yoshihide who looses his mind in the process of creating a folding screen depicting the Buddhist hell. Akutagawa’s macabre aesthetic is also one of the main features of Bungo’s antagonist Akutagawa: the sickly, pale-skinned member of the mafia is always wearing dark clothes with a slight aristocratic touch and his ability, “Rashomon”, allows him to summon a phantom-like creature from his coat.

The same character-modeling principle (i.e., developing characters based on famous writers and their works), applies to the American and the Russian part of Bungo’s character repertoire. Bungo’s F. Scott Fitzgerald, a young millionaire and leader of the North American organization called The Guild, parades through the streets of Yokohama together with his fellows H. P. Lovecraft and Nathaniel Hawthorne just as the ‘real-life’ Fitzgerald’s Gatsby probably paraded through the streets of New York City during the Roaring Twenties. The Russians, Ivan Goncharov and A. S. Pushkin, are grouped together in an underground secret organization called Rats in the House of the Dead (the name is a reference to F. M. Dostoevsky’s novel The House of the Dead (1862)), led by the mastermind Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose ability is none other than “Crime and Punishment”, inspired by the Russian writer’s famous work.

All these different characters’ encounters on the streets of Yokohama, whose night scape is beautifully depicted in classically neon, cyberpunk tones, generate a unique atmosphere in which different cultures collide; E. A. Poe struggles to outwit his Japanese counterpart Edogawa Ranpo, while Herman Melville is gliding above them and the Yokohama skyline in Moby Dick, The Guild’s official aircraft (you can probably guess it’s in the shape of a whale).

But besides letting you pick up a few names from Japanese, American, or Russian literature, Bungo Stray Dogs has few more things to offer. The dynamic between the various literary-inspired characters creates original (although sometimes a bit complex, and sometimes a bit dark) plot lines. For example, while the initial plot line largely centers on Nakajima Atsushi, who was kicked out of an orphanage and has no food and no place to go but suddenly runs into Osamu Dazai and his partner Kunikiada who are tracking down a loose tiger that appeared in the area (the tiger later turns out to be Atsushi himself), the initial focus on Atsushi, who nevertheless remains one of the central figures of Bungo’s story world, gradually fragments into several plot lines which follow the Armed Detective Agency’s encounters with the Port Mafia, The Guild, and, later, the Rats of the House of the Dead. The perspective also frequently changes from that of the detective agency to a close-up view of the mafia’s business, which allows us to discover some elements of the characters’ dark past. Finally, although Bungo Stray Dogs is generally not a ‘dark’ anime (apart from some bloody visuals here and there), it does get pretty dark in Bungo Stray Dogs: Dead Apple with the introduction of the antagonists Tatsuhiko Shibusawa and Fyodor Dostoevsky as special ability users in Yokohama and all over the world suddenly start committing suicides.

All in all, even if anime and manga are not really your thing, but you do have an interest in literature and cross-cultural encounters of all kind, I would definitely recommend giving Bungo Stray Dogs a go. The series is pretty unique in the way it plays with cultural figures from different parts of the world and engages them into unexpected encounters on the streets of Yokohama. Its underlying literary theme gives the otherwise ‘yet-another-action-anime’ an original touch and might end up being just right for all the ‘less-anime-and-manga-inclined’ bookworms out there.

Sources:

1. Valdez, Nick. “Bungo Stray Dogs’ Season 3 Shares New Poster.” ComicBook.com, 1 January 2019, https://comicbook.com/anime/2019/01/01/bungo-stray-dogs-season-3-poster/. Accessed 9 February 2019.